February 12, 2004

Hampton Grease Band

by Glenn Phillips

If a tree falls in the forest and there's no one around to hear it, does it make a sound? Listen to Music To Eat by the Hampton Grease Band, and you'll know the answer. At the time of its release in 1971, the HGB's double record was purported to be the second-worst selling album in Columbia Records' history (beaten only by a yoga record). It has since gone on to become a highly prized and costly collector's item, both in America and overseas.

The band's beginnings can be traced back to 1965, when guitarist Harold Kelling was playing high school dances with his group, The IV of IX. They used to haul their equipment around in an old funeral hearse, and their specialty was the instrumental hits of The Ventures. Kelling recalls, "Our bass player told us that a school friend of his named Bruce Hampton was going to professional wrestling matches and had a mighty unusual sense of humor. He brought Bruce along to practice one day and with a lot of encouragement and some coercion he started coming to gigs." Hampton says, "It was completely an accident that I became involved with music. Harold called me on stage one night out of the blue."

Soon thereafter, Bruce started showing up at their jobs with a guitar, even though he couldn't play it at all. Harold would call him up on stage, and then hide behind the amps. The band would go into a song, with Harold playing out of the audience's sight. Bruce would stand up front with his guitar, and start jumping around and going crazy, making believe he was playing the guitar parts.

A year later, in 1966, I began playing guitar myself. One day at school I told Bruce, "I'm going to be the best guitar player in the world." Bruce responded, "I'm going to be the world's best vocalist." "Well," I said, "we ought to start a band together." When Harold's band broke up in '67, the three of us joined forces and became the creative core of the HGB. We asked my older brother Charlie Phillips to play bass and close friend Mike Rogers to play drums, despite the fact that neither of them had any experience on their prospective instruments.

Harold remembers, "I went to New York with Charlie and Bruce after the IV of IX broke up. We saw Frank Zappa on the street and I just walked up to him and said `Grease' with no particular context in mind. Somehow we communicated to him our compatible weirdness, and he invited us to the recording studio, where part of our conversation was recorded and used on `Lumpy Gravy'. We put `Grease' together with `Hampton' for the band's name because he was our only vocalist. He was not the leader. After we returned to Atlanta, we picked up on blues music. We wanted to play it, but there were no white blues bands anywhere in the South, so we were unique and alone."

We soon discovered that there were no clubs in our hometown Atlanta area that were interested in hiring us to play. Bruce observes, "We went through a lot of struggles just to get gigs, it was a pretty rough road." Eventually we did find a club that would have us, the Stables Bar & Lounge. It was there that a patron pulled a gun on Bruce in the middle of a set and told him to "play some James Brown or I'm gonna blow your fuckin' head off." Bruce turned around to the rest of the band and yelled out "Popcorn, parts 1 and 2!" The club was run by Abner Jay, who was paying us 50 cents each a night. He routinely advised us to "sell those goddamn guitars and amplifiers and buy you some pussy."

1968 brought the summer of love and a growing population of hippies to the Atlanta area. Our music had evolved into something quite different from what was considered "hip" at the time, possibly because most of the band never did drugs. Also, most of us came from troubled homes, and coupled with the energy and anger of youth, we had unconsciously adopted a very strong `us against the world' attitude.

We began playing regularly at the local underground club, The Catacombs, where the peace and love generation found themselves frequently under attack at our performances. The band's stage show had grown increasingly aggressive and Bruce would often throw tables and chairs into the audience. We also made a habit of swinging from the water pipes in the ceiling during our sets. One night the pipes snapped under our weight, and sprayed the audience with water. Harold describes the band as "building such insane energy that we'd just fly off the handle."

The band was also performing at Piedmont Park, a large park near downtown Atlanta. Prior to us, no other electric band had played there before, so the city never bothered to turn off the power to the outlets. We'd just drag our equipment down there, set up, plug in and play. The local underground street paper, The Great Speckled Bird, began to promote our free shows at the park, and the hippie movement started to embrace the band. Before long, the park shows became major events. Other local groups and more well-known national acts began playing there with us. We did numerous free concerts with The Allman Brothers, as well as with Spirit and The Grateful Dead. A few hours before one park show, a struggle between the hippies and the police erupted into a riot. All of us, except Bruce, managed to sneak through the police lines and performed amidst the haze of tear gas that had engulfed the park.

Harold and I constantly pushed each other to greater heights as guitarists, and it was only a matter of time before we began to have the same effect on each other as songwriters. Harold comments, "Glenn and I started to pursue a broadened and more eclectic compositional mode. This evolved gradually and came to its head with the material on Music To Eat." We were writing long involved pieces of music, usually without words. When we showed them to Bruce, who was never involved with the writing or arranging of the band's music, he was often at a loss for lyrics. One day while we were playing Harold's song "Hendon", Hampton picked up a can of spray paint and began reading off the label. Another time, I was trying to show Bruce the melody to a new song of mine that didn't have lyrics. We opened up the encyclopedia and began pulling lines from the page on Halifax.

Harold says, "Some people who hear the band have absurd ideas about the meaning of the lyrics, talking about `psychedelicized multi-level innuendo' and `mystical revelation'. Horsefeathers. Some of the lyrics are obviously lifted from printed material, but most of it was a tribute to friends, inside jokes and playful abstractions-with the possible exception of `Hey Old Lady', which was about a mentally ill old lady who did just what the song says. Charlie Phillips wrote the lyrics to that one, while Glenn wrote the music and lyrics to `Maria'. The song `Six' however does contain some veiled references to a very bizarre and unexplained series of events that occurred to Bruce and I on June 6, 1966. Overall though, the lyrics have about as much philosophical depth as a sheet of Saran Wrap."

The band's sound was also influenced by the personnel changes we had gone through. Charlie had been replaced by Mike Holbrook on bass, and after going through several drummers, Mike Rogers was eventually replaced by Jerry Fields. Although Charlie and Mike were integral to the formation of the band, they weren't naturals on the instruments we had thrust upon them. Considering they had never played before we asked them to, they did an incredible job, but as our material grew more complex, we needed someone else.

When we worked up our material with Mike and Jerry, they infused the music with their own energy and ideas. Jerry elaborates, "We got into playing with different time signatures simultaneously. There are sections in `Evans' that are like that. Half the band would be playing in 5/4 while the other half was in 4/4. It would create a tension and then it would resolve every 20 beats (4 bars of 5, or 5 bars of 4 equals 20). Everything would be going apeshit and it seemed like everybody was doing their own thing and all of a sudden we'd just hit this one place at the same time."

We began to play out more and more, doing everything from small clubs to pop festivals with audiences of over 300,000. We played with Jimi Hendrix, Captain Beefhart and the Magic Band, the original Procol Harum (the best live band I ever heard), Mahavishnu Orchestra, Peter Greene's Fleetwood Mac (the loudest band we ever played with), John Mayall, N.R.B.Q. (the first time Al Anderson played with them), B.B. King, and Country Joe and the Fish. We started the Country Joe concert by shouting at the audience, "Give me an S, Give me an O, Give me an F, Give me an A. What's that spell?"

Mike Holbrook describes his first road trip with the band. "We were playing in Charlotte, N.C. We got there early, and it was raining and drizzling. We went out walking in the rain, and came upon a junk yard. We gathered up car parts and junk and dragged it all back to the club. We put it all on stage and then put our speakers on it. The whole stage was covered in junk. When we played that night, Bruce came out and had on shorts and flip flops and sang standing on a pizza. Then we went up to New York, driving in my old van that had a piece of pipe for a gear shift lever. We got there at 8:00 in the morning, right at rush hour. We were in the middle of the Holland tunnel when the gears to the van locked up. We blocked up traffic all through the tunnel. Bruce got out and crawled up under the van to pull the linkage, and he pulled out a yoga book of Jerry's. That's what caused the linkage to lock. Then we drove off real fast and ran into a bus."

Our shows grew increasingly weirder. The stage was frequently filled with friends doing anything from watching TV, doing a duet with the guitar on a chain saw, or sitting at a table eating cereal. Hampton, who at one point sported a crew cut with an H shaved in the back of his head, would tape himself to the microphone stand while talking to the audience about the supposed Portuguese invasion of the U.S. through Canada. At an outdoor show, Bruce slept through our set under a truck, while at another show, he turned around in the middle of a song, jumped in the air, and kicked Mike in the chest. Mike flew back into his amp, which he knocked over and short-circuited. Holbrook recalls another time when "we got the idea that we wanted to put mayonnaise all over our friend Eric Hubbler. We got a gallon of mayonnaise and Hubbler came out and sat down in a chair while the band was playing. I stuck my hand down in it and glopped it all over his head."

One night at The 12th Gate (our favorite local club), drummer Jerry Fields stood up in the middle of a song, froze motionless and stared off into space. We played the rest of the set without drums, and he stayed that way for over an hour, until everyone had left the building. Jerry recalls, "I went into a trance and I mentally told myself I wasn't going to move till everybody had left. I got way out, I don't know how I did it. People we're asking if I was ok, and wondering if they should call a paramedic. I just held that pose while the rest of the band was going apeshit. Hampton was literally climbing the walls. He was up in a corner near the ceiling with one foot on each wall, in a split with a microphone. There was a booking agent in the audience that night to hear us. After the show he told our manager `I don't know what they sound like, but I guess it doesn't matter'."

People seemed to either love the band or hate it. Harold recalls the time the band was chosen to warm up a crowd of ten thousand people at a Three Dog Night show in Alabama. "We went on stage and opened with `Apache' (a Ventures song). At the end of the song, the audience was hushed. They didn't know how to react to us. We went into `Evans' and about halfway through we heard the bleachers banging and people yelling and ranting. Then they started throwing jawbreakers and cups of ice at the stage." Holbrook, who was hit in the head with a flying object, remembers Harold going to the mike and telling the audience "C'mon down here, and I'll whip your ass."

At another show, we opened up for Alice Cooper in New Jersey. At the end of our set, half the audience was booing for us to get off, and the other half was yelling for more. As their cries grew louder and louder, they started standing up and yelling at each other, instead of at the band. It got so bad that the house lights had to be turned on and the ushers had to break up the crowd.

Columbia Records had heard about us, and was interested in signing the band. They didn't know how to contact us, so they called up Phil Walden, the head of Capricorn Records in Macon, and asked him if he knew how to reach us. Walden told them that the HGB was signed to a production deal with his company, despite the fact that none of us had ever met him. The band was in fact signed to Frank Hughes and Steve Cole, two well-intentioned but inexperienced local promoters who ran Discovery Inc. As soon as Walden got off the phone with Columbia, he contacted Discovery and told them that if the HGB signed with him, he thought he could get them a deal with a major label. Hughes and Cole went for it, and convinced us to sign with Walden. Both Discovery and the band were too naive to know we could have signed to Columbia without Walden's involvement. Walden recalls, "Some people at CBS were interested in the band because their Atlanta Pop Festival performance had a lot of people talking. I knew the two young guys who were handling the band, so when CBS called me, I called them up and we put the deal together."

Columbia advanced $75,000 for recording and promoting the band--a large amount at that time for a group's first effort. By the time the money made its way through the band's new "business arrangement", all that was left for recording and promotion was $17,000.

We went into the studio with recording engineer and close friend David Baker on Halloween weekend of 1970 (three years after the band had started). We recorded one album's worth of material (`Halifax', `Hendon' and `Evans'). Holbrook comments, "We did the whole thing in a couple of days. On `Hendon', we played straight through and only did one take. Right before we went into the studio to do `Halifax', Glenn added all of these little parts to it. We worked those things up in about 2 days. It was real quick. When I listen to it now, I wonder how in the hell did we do that? I mean, the song's 20 minutes long and there's a zillion parts and they're all different."

Jerry remembers us "recording it on an old 8 track that only had 5 tracks working. David Baker was real skeptical about the tape machine working at all. That's what he's talking about when you hear him say `Do it again, I don't trust this tape recorder' at the end of `Halifax'. We also had all these people in there for the yelling at the end of `Evans'. They were just walking around opening and closing doors, and you can hear some of that on the record." Mike remembers "everybody sitting around listening to the end of `Evans', the part where just Glenn and Harold are playing together. Everybody in the room knew that it was great. That moment stands out as a real point in time."

We sent the tapes to Columbia and they didn't know what to make of the music. The shortest song we sent them was 18 minutes long, and to them, it all sounded incredibly weird. They wanted something shorter and more commercial so they could get the record played on the radio, but they felt it was hopeless to try dealing with us. As one Columbia exec put it, "They were the straw that broke the camel's back, the most outrageous group anybody here ever had to deal with."

Columbia came up with the idea of releasing a double record, in hopes that if we had to do another album's worth of material, something on it was bound to be more commercial. They also sent down their new employee, Tom McNamee, to try to "work with the group". Unfortunately for Columbia, Tom was actually a fan of the band and had no real interest in trying to make us more radio-friendly. We recorded `Six', `Maria', `Hey Old Lady/Burt's Song, and two improvisational pieces that each featured one guitarist, instead of our usual double guitar lineup. `Lawton' was a one-take, live improvisation in the studio between myself and Jerry, while Harold's jam with Mike and Jerry occurs midway through `Six'. When we finished the 2nd album's worth of material, we sent it to Columbia. After they heard the tapes, Tom was fired.

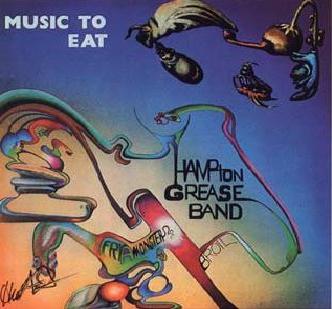

Harold then began to put together the cover artwork. The front cover was a painting he had done with Espy Geissler. He filled up the inside with pictures of our friends. You couldn't tell who the band members were from the pictures. The largest photo was of four old high school friends with a drawing of a green lizard-guy in a suit, looking at them and saying "The 4 people (fraben) pictured here have complete control of the North American continent at this very second." The band's road manager Sam Whiteside (pictured with the acoustic guitar on the inside cover) drew the lizard and also most of the other inside art. There's also a reprint of a bad review of one of our shows which read in part:

On stage with the Grease Band were friends who danced, watched TV, listened to the music and marched around stage as if at home in their living room. One girl even read a book and another sewed on an American flag during the Grease Band's performance.As to their `music'--and I use the term loosely--the band performed much the same way. Very little of what they did had any context within itself. The casual actions on stage relayed directly to the audience and caused wandering, talking and virtual unrest.

When Harold showed me what he had for the cover, I told him, "it's great, but this is for a double record. You need four pieces of cover art, but you've only got three. You don't have a back cover." He looked up and noticed a picture of a tank hanging by a thumbtack on his wall. He had drawn it years ago back in high school. He pulled it down and said, "we'll use this."

When Music To Eat was released in 1971, it received very little support from the label. Columbia felt they had already put out the money for promotion to Walden, but he didn't seem interested in putting any of the money he'd made on the band into promoting the record. Both Columbia and the band felt cheated.

Complicating things further, the sales people at Columbia didn't know what to make of the record. They frequently marketed it to stores as a comedy album, where it was filed alongside Don Rickles and Bill Cosby.

In a desperate attempt to try to straighten things out, our manager, Frank Hughes, began to hold frequent meetings with the band. Before the meetings, the band would make up a catch word, like "strenturgent". We'd use the word throughout the meeting, to see if we could get Frank to start using it. We'd continually complain of Columbia's "strenturgent" treatment of the group and by the end of the meeting Frank would be saying, "I don't think Columbia is treating the group strenturgently."

Holbrook recounts another incident. "We were at the Chelsea hotel in New York and Frank was on the phone doing all his business stuff. He was getting ready for a big CBS meeting and had his papers spread out all over his bed. Bruce came in the room and poured water all over them. Frank went nuts and Bruce started cackling." In retrospect, Frank was one of the best friends the band ever had, although I'm not sure he feels the same way about us.

Soon after the record came out, the band encountered a more serious problem than our relationship with the record company. We began to degenerate into petty infighting. We were all incredibly close and would sometimes argue, but things had grown worse and escalated to the point where Harold and the group split apart. Harold comments, "We began to go in different directions musically as well as spiritually and as these tensions increased, a split was inevitable." Although we had survived several personnel changes in the past, losing one of the 3 founding members was devastating to the band's chemistry. Although we continued playing for another two years, it was the beginning of the end of the Hampton Grease Band. I remember going home after the split and crying for a long time.

The band continued on, sometimes just the four of us, and other times with a different fifth member. Mike Greene (who went on to become the president of NARAS, the organization responsible for the Grammys) played with the band for a while, as did Syd Stiegal. Syd was a classical pianist who had never played a band job in his life. His first job with us was at the Fillmore East. Duane Allman, who was a fan of ours, had told Bill Graham that he should book us. We played there with Frank Zappa and The Mothers of Invention, the weekend that John Lennon sat in with them and they recorded a live album.

We played 2 nights and did 2 shows a night. We were told that we went over better than any new band that had ever played there. Kip Cohen (who ran the Fillmore East) wrote a letter to Clive Davis (who was at that time the head of CBS):

Dear Clive:As you know, this is the first time I've ever written a letter like this one to you--but even though John Lennon and Yoko Ono guested on our stage last night, my memories of the past weekend will reside exclusively with the Hampton Grease Band.

Aside from their totally delightful, unique brand of humor, and the obvious fact of their being good people, there is a musical intelligence within that band that truly excites me.

I can only hope that they enjoy the total success they deserve. They were one of the most pleasant surprises we have had on our stage in many, many months.

An internal CBS memorandum to Clive Davis dated June 8, 1971 reads:

The Hampton Grease Band's Fillmore appearance on the weekend of June 5/6 was a total success. They received two encores and a standing ovation for every set they played.Kip Cohen searched me out to tell me that the HGB members are among the finest musicians ever to grace the stage at the Fillmore. Glenn Phillips, their guitarist, was involved in a jam session with Frank Zappa and his enthusiasm was equal to that of Cohen.

The Hampton Grease Band could become cult heroes with the right kind of publicity.

The Fillmore job was a welcome morale boost. It was one of the only positive things that had happened to the band in a while. When we returned to Atlanta though, we were surprised to discover that neither our booking agency nor anybody at CBS would take our calls. To put it in the vernacular of the music business, the record company pulled the plug. Maybe CBS was pissed because they felt burned by the Walden deal, or maybe it was because they felt we were just too weird to deal with. After CBS dropped the band, we signed with Frank Zappa and Herb Cohen's Bizarre/Straight label and management. Although Frank was very supportive of the band, our experience with Herb was a complete nightmare. At one point, he actually sent the guy who produced `Snoopy versus the Red Baron' to try to produce us.

In 1973, Bruce heard that Frank Zappa was holding auditions for a vocalist. He quit the band and went to California to try out, but didn't get the job. Although I was disappointed when Bruce left, in retrospect I'm glad he did. The band broke up as a result of his leaving, and had he stayed we probably would have made a second record. To be honest, if we had recorded at that point in time, I don't think it would have been very good. I'm glad that Music to Eat is left on its own to represent the times that the band shared. We were all incredibly lucky to have run into each other when we did.

Trying to sum up what the Hampton Grease Band was all about is difficult. It was an intensely musical group with an intensely non-musical singer, or as Jerry Fields put it, "music versus anti-music". We were also definitely a product of the 60's, yet we were oddly out of step with the times. I guess this joint interview with Harold, Bruce, and myself from 1968 explains us as well as anything could.

What's Grease?

It's a concept of music.---It's a concept of life.---It means lobster eggs and ointment.---It means basically to suck, yeah, basically to suck.---It's hard to define.--- See, our main ambition in life, aside from growing a bosom on top of our heads is to die on stage. When we die on stage that will be when we ultimately reach Grease.

What kind of music is it?

Suckrock. It's a combination between suckrock and ointment.---It's all a form of eggs; it all leads back to eggs.---The goal is complete expression. When you completely attain this expression, you won't sound like anybody. You have your own sound and you just destroy. What we want people to do is just come in and hear Grease and to destroy.---Yeah, that's it.

Since the band's breakup:

Harold Kelling formed the Starving Braineaters after he left the HGB, and released a single under his own name in 1982. He's currently playing with two groups - Creatures del Mar, and Masters of the Edge.

Bruce Hampton formed the Hampton `Geese' Band after he left the HGB. He later re-signed with Phil Walden, and released two albums with The Aquarium Rescue Unit. He's currently performing with the Fiji Mariners.

Glenn Phillips has released 10 instrumental albums, including the double CD retrospective Echoes. He also plays with the Supreme Court, whose recent CD featured cover art by Harold Kelling.

Mike Holbrook played with the Mike Greene Band, who released two albums in the 70's. He currently plays part time with the Supreme Court and the Glenn Phillips Band. He appears on two of Glenn's albums.

Jerry Fields went back to college, where he graduated with a degree in music. He was a member of the Late Bronze Age with Bruce, and played on their recording, as well as on three of Glenn's albums. He also teaches percussion.

Special thanks to:

Phil McMullen, for his in-depth interviews both with myself and Harold Kelling, which were printed in his superb publication Ptolemaic Terrascope. They were invaluable.

I also drew freely from other articles on the band, including those written by Tony Paris, Jeff Calder, Mitchell Feldman, David T. Lindsay, The Great Speckled Bird and The New York Times.

I also greatly appreciated the band members taking the time to let me interview them. They were essential in my attempt to accurately recount the band's history.

Frank Hughes and Steve Cole for putting up with an endless barrage of bullshit from the band.

Bill Fibben, Carter Tomassi, Miller Francis, Linda Fibben, Cliff Endres and everybody else at The Great Speckled Bird. It's hard to imagine the HGB without their friendship and support.

Charles Mingus, for coming to our album release performance in New York, even if it was just for the free food.

Lastly, thanks to my dad. Although he initially disapproved of the band, when the record was released he took it to the main building of his company, Metropolitan Life Insurance, in New York. He tapped into the skyscraper's sound system and played the double album non-stop throughout the entire work day.

© 1996 Glenn Phillips / all rights reserved. The Hampton Grease Band is also featured in the book, "Unknown Legends of Rock n' Roll" by Richie Unterberger.

CREDITS:

HAROLD KELLING-guitar, vocals

GLENN PHILLIPS-guitar, saxophone

BRUCE HAMPTON-vocals, trumpet

MIKE HOLBROOK-bass

JERRY FIELDS-percusion, vocals

CD 1 (69:10)

1. HALIFAX (19:36)-music by Glenn Phillips lyrics by Glenn Phillips and Bruce Hampton

2. MARIA (5:27)-music and lyrics by Glenn Phillips

3. SIX (19:31)-music by Harold Kelling lyrics by Harold Kelling and Bruce Hampton

4. EVANS (17:48)-music by Harold Kelling and Glenn Phillips lyrics by Bruce Hampton

5. LAWTON (7:48)-Glenn Phillips and Jerry Fields

CD 2 (51:50)

1. HEY OLD LADY/BURT'S SONG (3:19)-music by Harold Kelling lyrics by Charlie Phillips and Bruce Hampton

2. HENDON (20:13)-music by Harold Kelling, Glenn Phillips, Jerry Fields and Mike Holbrook lyrics by Bruce Hampton